Las Meninas

by Bruce High Quality Foundation

Material

silkscreen and paint on canvas; 259.1 x 228.60 cm

Dating

2011

About the artwork

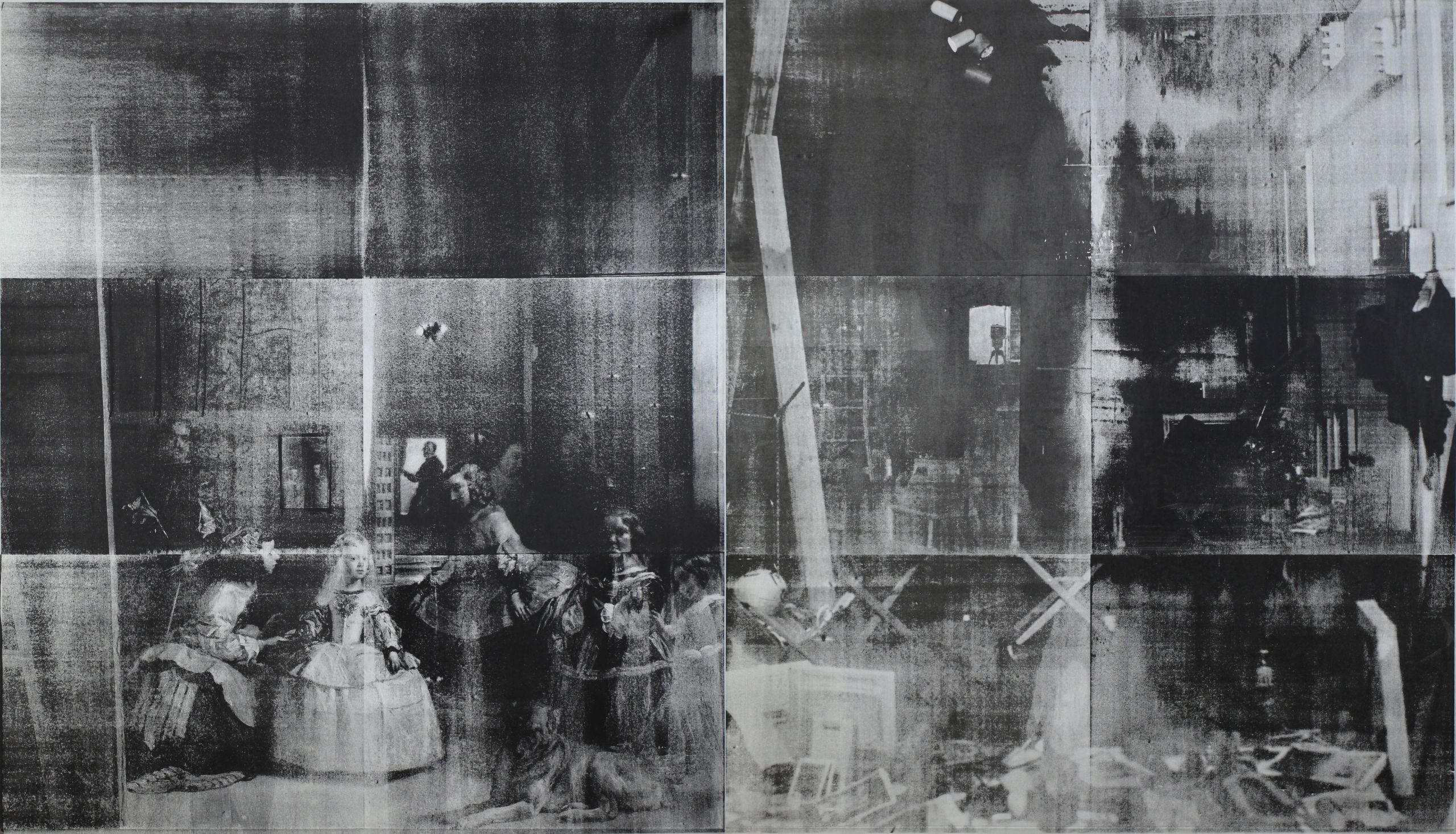

Las Meninas, BHQF 2011

By appropriating notoriously works from the past and creating a charged dialogue with the present, BHQF aims “to invest the experience of public space with wonder, to resurrect art history from the bowels of despair, and to impregnate the institutions of art with the joy of man’s desiring’. The overt appropriation in this work, unabashedly simply titled Las Meninas, is multifarious in terms of the iconographic and the aesthetic. First, with analogous titles, the left panel of the diptych is a reproduction of the 17th-century painting by Velázquez. The group portrait of the Spanish royal family (and the inclusion of the self-portrait of the artist at the easel) is as stated before iconic.

The relationship between subjects and the viewer, between reality and (self-) representation, are reinforced and brought up in a intrigued way. As Velázquez presents himself in Las Meninas as an unrivalled painter welcomed into the royal sphere, the appropriation of the work refers back to BHQF’s rejection of the "celebrity artist." Las Meninas (2011) is juxtaposed with a silkscreened photograph of the BHQF studio, notably absent of any artist, however, scattered with materials of art production. Both versions of Las Meninas are paintings regarding notions of the artist, the processes of art-making and ultimately reveal the complex interaction with the viewer.

Formally, the black on silver silkscreening application of BHFQ’s Las Meninas also serves as a visual allusion to Andy Warhol’s seminal silkscreens of the sixties. By using visual codes, BHQF’s specific reference to Warhol is used to further articulate the role of the artist. Warhol serves as the clear precursor to the contemporary status of superstar artists with fame, celebrity and notoriety delineating key themes in Warhol’s work. Thus, through appropriation of iconography and style from icons of the past, BHQF formulates a cohesive dialogue about contemporary art practice today.

"It’s been important for us to think of art history as a material, as more stuff to work with, whether it’s to honor or to disparage it. It’s as much a material as anything else, wood or plaster." (BHQF in an interview with Cameron Shaw, ‘Enter the Afterlife: A Conversation with the Bruce High Quality Foundation’, Art in America, March 2009).

Diego Velázquez’s version of 1656

Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things: An Archaeology of Human Sciences (published in 1966 and translated in English in 1970) opens with an extended discussion of Diego Velázquez’s painting Las Meninas (The Maids of Honour) and its complex arrangement of sight lines, hidden subject and appearance. By analysing Velázquez’s most famous painting, Foucault develops the central claim of the book, i.e. all periods of history have possessed certain underlying conditions of truth that constituted what was acceptable as, for example, scientific discourse. Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, in major and relatively sudden shifts, from one period to another.

The work’s complex and enigmatic composition raises questions about reality and illusion, and creates an uncertain relationship between the viewer and the figures depicted. Las Meninas shows a large room in the Madrid palace of King Philip IV of Spain, and presents several figures, most identifiable from the Spanish court, captured, in a particular moment. Some figures look out of the canvas towards the viewer, while others interact among themselves.

The young ‘Infanta Margarita’ is surrounded by her maids of honour, chaperone, bodyguard, two dwarfs and a dog. Just behind them, Velázquez portrays himself working at a large canvas. Velázquez looks outwards, beyond the pictorial space to where a viewer of the painting would stand. A mirror hangs in the background and reflects the upper bodies of the king and queen. The royal couple appears to be placed outside the picture space in a position similar to that of the viewer. A few critiques even suggested that they were being painted by the painter.

Las Meninas is a pure manifestation of critical thinking, an important trait of modern philosophy. The value of Valasquez’s painting for Foucault lies in the fact that it introduces uncertainties in visual representation at a time when the image and paintings in general were looked upon as "windows onto the world." Foucault finds that Las Meninas was a very early critique of the supposed power of representation to confirm an objective order visually. This close textual analysis is an excellent introduction to the following enveloping treatise on the "order of things."’ He finds a paradoxical relationship between reality and representation.

Foucault constructs a triangular relationship between the painter, the mirror image, and the shadowy man in the background. These three elements are linked because they are all representations of a point of reality outside of the painting. In his analysis, what is outside the painting gives meaning to what is inside. Therefore, the King and Queen is the centre of the scene. They create this spectacle-as-observation by providing the centre around which the entire representation is ordered; they are the true centre of the composition.

These three observe the scene depicted in the painting at different times, but from the same place in space. The three perspectives belong to the King and Queen (who are looking at this scene as they are being painted), Velazquez (the painter of the scene, presumably after the scene has occurred), and we the spectators (who are looking at the finished painting). The models are seen in the mirror; the painter is self-portrayed on the left side; the spectators are represented by the shadowy figure in the back about to enter or exit the studio.

The painting ‘Las Meninas’ is a peculiar in the sense that it is a self-aware painting. The painter paints himself, he paints his own act of painting and the object on which the painting is subjected, holds authoritative control including representation. In this painting the subjects who are invisible to the spectators hold a dominating presence than the actual figures including the painter. The canvas occupies a significant portion of the painting, taking up almost a whole vertical strip of the far left side, and cleverly hiding the corners of the room.

The canvas is not looking at anything, unlike all the other characters of the painting. The model’s representation in Las Meninas, then, becomes even more complex. The canvas is a modified copy of the model (the King and Queen). Further, the representation of the model in the mirror can only be seen from our (the spectator’s) perspective, and not the model’s. In fact, the model looks into the mirror and sees nothing, while we can see the reflection of the painted model in the mirror. We know of the model’s presence through the mirror, but the unseen canvas interrupts the direct relationship between the mirror and the model.

Foucault examines the power of representation over reality. The language is terse and creates the perfect atmosphere where we start behaving like spectators viewing the painting. The only point of reality reflected within the painting which is the subject on which the painter is painting, is shown to be invalid. The focus of the painting forever vacillates between multiple planes of form and meaning, all within the painting itself. Illusion and reality are confused. And in the end, we cannot say that what we see is the truth because it is only part of the illusion.

About the artist

The Bruce High Quality Foundation is an arts collective that was formed in 2004 in Brooklyn, New York City, and which was "created to foster an alternative to everything." The group is named after a fictional artist, the sculptor "Bruce High Quality", who supposedly died in 2001. Its members remain anonymous, in protest against the "star-making machinery of the art market", but it is known that they are a group of artist that met and became friends while studying at Cooper Union (New York).